Most mouth breathers assume the issue is obvious. They sleep with their mouth open. They wake with a dry mouth. They might snore.

What many don’t realise is that something more structural is happening while they sleep — something that affects how stable their airway is throughout the night.

During sleep, mouth breathing doesn’t just change where air enters. It changes how hard the airway has to work to stay open.

In sleep medicine, nasal and mouth breathing are considered different physiological states, not interchangeable habits.

The nose plays an active role during sleep. It:

When nasal breathing becomes difficult — due to congestion, allergies, or anatomical restriction — the body often switches to mouth breathing as a temporary bypass.

Research shows that this bypass is functional, but not ideal.

Clinical studies have found that breathing through the mouth during sleep is associated with significantly higher upper airway resistance compared to nasal breathing. One well-cited study reported airway resistance to be around 2.5 times higher during oral breathing at night.

This means the airway must work harder just to stay open.

For a plain-language overview of why nasal breathing matters during sleep, see:

https://www.sleepfoundation.org/how-sleep-works/nasal-breathing-vs-mouth-breathing

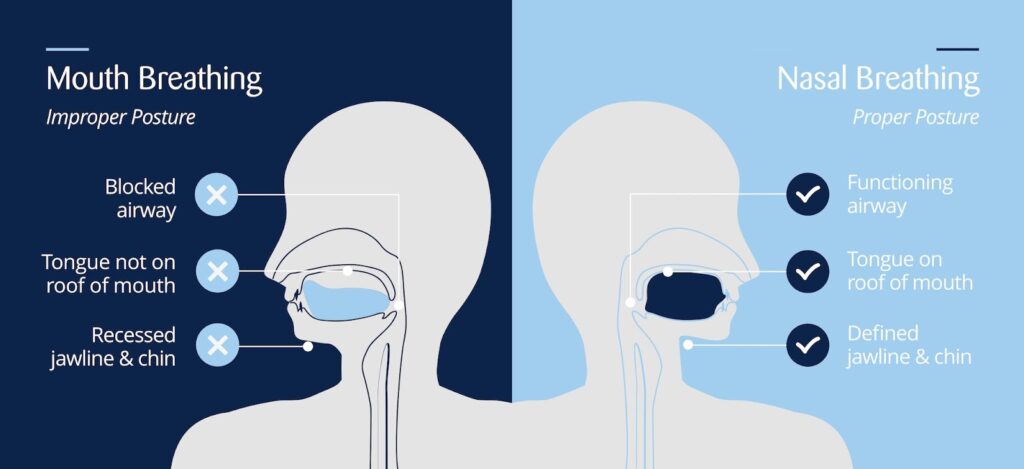

Image credit – https://www.mewing.app/blog/mouth-breathing-vs-nose-breathing

One of the least understood parts of sleep breathing happens inside the mouth. The tongue is a large, powerful muscle. When it rests gently against the roof of the mouth, it helps support the airway behind it.

During sleep, if that upward tongue posture isn’t maintained, gravity causes the tongue to relax backward. This can narrow the space available for airflow and make the airway more prone to partial collapse.

Physiological research shows that mouth breathing is associated with reduced activation of key tongue muscles during sleep, particularly in adults. As muscle responsiveness drops, the airway becomes less stable — even if breathing never fully stops.

This explains why some people:

A common assumption is that mouth breathing only occurs when someone sleeps with their mouth open.

In reality, breathing patterns are driven by habit, muscle tone, and airway comfort, not just lip position.

Sleep studies show that oral airflow can occur:

This means some people breathe through their mouth during sleep without realising it, even if their lips appear closed.

Many mouth breathers don’t describe their sleep as “bad.” They just don’t feel restored.

Research has linked nocturnal mouth breathing with:

In children, the association appears even stronger.

A large clinical study found that children who primarily breathe through their mouth were over four times more likely to screen positive for sleep-disordered breathing compared to nasal breathers. Parents in these studies frequently reported symptoms such as:

These findings align with guidance from paediatric sleep and dental organisations, including the NHS, which notes that persistent mouth breathing in children can be linked to sleep and behavioural concerns: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/mouth-breathing/

📊 What The Research Shows

A comprehensive analysis of multiple studies found consistent skeletal differences in mouth-breathing children, including measurably narrower airway spaces and altered jaw positioning. The statistical association is robust: children showing these patterns had a Relative Risk of 4.24 for positive sleep-disordered breathing screening scores.

Data from systematic meta-analysis by Zhao et al. (2021) and Saptarini et al. (2025)

During childhood, the face and airway are still developing.

Craniofacial research shows that chronic mouth breathing during these years is associated with measurable differences in jaw position, facial growth patterns, and airway space. Over time, these structural changes can reinforce the very breathing patterns that caused them.

This doesn’t mean mouth breathing “causes” sleep disorders outright — but research consistently shows it is a significant risk factor, especially when the habit persists after nasal obstruction has resolved.

Chronic mouth breathing is often associated with reduced tone in the tongue and throat muscles.

Clinical research into myofunctional (oral muscle) training has shown that improving tongue and airway muscle responsiveness can support more stable breathing during sleep. In published studies, structured muscle-based interventions were associated with clinically meaningful improvements in sleep-disordered breathing measures in both adults and children.

These findings are why many clinicians now view sleep breathing as something influenced by patterns and function, not just anatomy alone.

For a general, non-technical overview of sleep-disordered breathing, see: https://www.sleepfoundation.org/sleep-apnea

Mouth breathing during sleep isn’t just about air entering through the mouth. It reflects:

For many people, understanding this is the first step toward making sense of long-standing sleep concerns that never seemed to have a clear cause.

This article is informed by peer-reviewed research in sleep medicine, dentistry, and airway health, including systematic reviews and clinical studies, as well as guidance from recognised health institutions such as the NHS and the Sleep Foundation.

It is intended for educational purposes only and does not replace personalised medical advice or diagnosis.

For some people, becoming more aware of breathing patterns is the first step. Others choose simple tools designed to encourage better oral posture and nasal breathing habits as part of a broader, research-informed approach to airway health.

Build the Self-Help Hub you need

Take our 1-minute survey to share your needs and get early access + a bonus when we launch.

You're now part of our rewards program! Start earning points and rewards with every purchase.

Start earning pointsCreate a free account to start earning points and unlocking member-only perks.

Already have an account?

Welcome back! Sign in to access your rewards.

Don't have an account?

Share your link with friends. They get a reward and you earn one when they purchase.

You were sent a gift

You have received

Use at checkout on your first order

Enter your email to claim it now.

Already have an account?

Already have an account?

When friends shop using your referral link, you'll see their activity here

Pending

Requires an account to redeem

Redeem rewards now

Turn your into discounts and perks

Instant setup

One click and you're ready to go

Earn even more

Get +100 bonus for signing up

Redeemed

Use this coupon on your next order

Free product applies automatically.

Start earning to unlock your first reward

This product is currently out of stock

Your reward will remain available when the product is back in stock.

Free product applies automatically.

You're now part of our rewards program! Start earning points and rewards with every purchase.

Start earning pointsCreate a free account to start earning points and unlocking member-only perks.

Already have an account?

Welcome back! Sign in to access your rewards.

Don't have an account?

Share your link with friends. They get a reward and you earn one when they purchase.

You were sent a gift

You have received

Use at checkout on your first order

Enter your email to claim it now.

Already have an account?

Already have an account?

When friends shop using your referral link, you'll see their activity here

Pending

Requires an account to redeem

Redeem rewards now

Turn your into discounts and perks

Instant setup

One click and you're ready to go

Earn even more

Get +100 bonus for signing up

Redeemed

Use this coupon on your next order

Free product applies automatically.

Start earning to unlock your first reward

This product is currently out of stock

Your reward will remain available when the product is back in stock.

Free product applies automatically.

Notifications